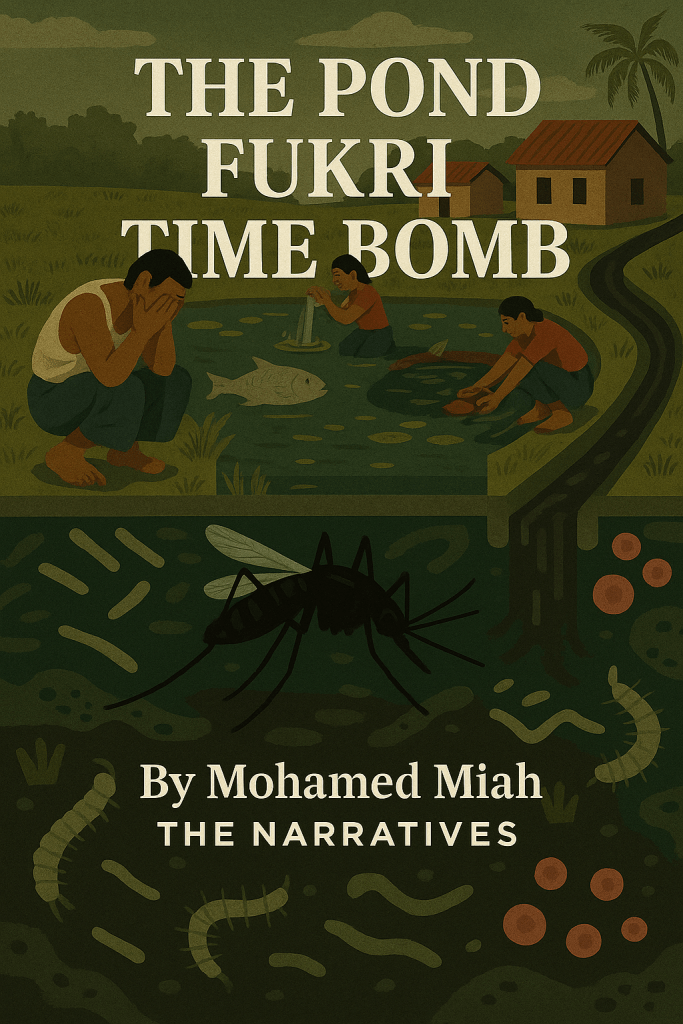

By Mohamed Miah | The Narratives

Once a blessing, now a trap

Scattered across Bangladesh, nestled behind homes and rice fields, you’ll find the fukri — a village pond, often dug by ancestors as a simple way to survive. It was never glamorous. It wasn’t designed. But it worked.

The fukri gave water where taps didn’t exist. It was used for bathing, washing clothes, sometimes for drinking when boiled, and it even provided fish when nothing else was available. In those days, life was hard. Only the fittest survived, and survival meant adapting to whatever was around you. People used the fukri because they had no choice — and their immune systems became tough enough to handle what came with it.

It was never clean. It was never safe. But the strong carried on, and the weak either left, adapted, or died quietly. No one called it a public health crisis. It was just life.

What’s changed — and why it’s worse now

Today, the fukri is still used — perhaps more than ever.

But now the danger is different.

People don’t just bathe or wash anymore. They feed fish in it. They pour feed, antibiotics, chemicals, and cheap supplements into the water to fatten fish for sale or family food. Leftover waste collects at the bottom. Human bathing mixes with animal waste. Uncovered drains overflow into the same water, especially during monsoon.

And the pond doesn’t filter any of it. It just sits. Stagnant. Swelling with bacteria, antibiotics, parasites, and mosquito larvae.

The same people — and their children — bathe in that water. Cook with it. Wash cuts and wounds with it. Their skin absorbs it.

That water now enters the bloodstream.

And because antibiotics are being poured in, resistance is being bred.

In fish.

In humans.

In insects.

You don’t need a medical degree to understand what happens next.

The perfect recipe for catastrophe

The fukri has become a petri dish.

It holds the conditions for a superbug. For the next incurable virus.

All it needs is time.

Stagnant water.

Mosquitoes.

Toxic runoff.

Unregulated fish farming.

Human and animal skin in the same supply.

And a reliance on cheap antibiotics to silence infections rather than treat them.

It’s a soup. And it’s not theoretical.

All it takes is for one mosquito to bite a child with an infection, feed off livestock injected with medication, and then fly into the next village.

And mutate.

It won’t matter that it started in a quiet village.

Viruses don’t care where they begin.

They only care how fast they can move — and how many bodies are unprepared to stop them.

The bigger picture why the world should care

This isn’t just a rural health story.

This is about a global system designed to keep people poor, desperate, and dependent.

We keep these villages in survival mode.

We buy their fish for cheap.

We praise their “resilience” while denying them clean water, proper healthcare, or environmental protection.

We let them rely on fukris and generic antibiotics because it’s cost-efficient.

It keeps our prices low and our imports high.

But we forget one crucial thing: the virus that kills millions might come from the very pond we left them with.

Because this is what happens when you leave people no option but to live in toxicity.

You’re not isolating danger — you’re incubating it.

And it will come back.

When it comes, where will you hide?

The West thinks it’s immune.

There’s faith in skyscrapers, logistics, digital borders. But even during Covid, we saw the cracks — people dying alone while calling family over Wi-Fi, medicines running out, systems overwhelmed.

That was a warning.

What happens when the next disease doesn’t respond to medicine?

When it spreads faster, when it’s bred in chemical water and carried by an insect?

When antibiotics no longer work because we overused them in ponds and pills?

Where will the rich run when the air becomes unsafe?

When the origin isn’t a lab, but a pond no one paid attention to?

The pond will not wait

We created this system.

We allowed the poorest to live in it.

We built our luxuries on their low costs.

And now, we’ve left them in a state where their survival has global consequences.

The fukri is no longer about poverty or culture.

It’s about global collapse.

We either fix it now — by giving clean water, proper healthcare, fair wages, and environmental respect —

or we wait for what’s already coming.

Because once that virus escapes the pond, it won’t be a village issue, it will be a global issue.

Leave a comment